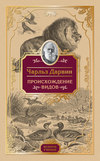

Читать книгу: «Life and Letters of Charles Darwin — Volume 2», страница 18

My work on Variation, etc., under domestication, will appear in a French translation in a few months' time, and I will do myself the pleasure and honour of directing the publisher to send a copy to you to the same address as this letter.

With sincere respect, I remain, dear sir, Yours very faithfully, CHARLES DARWIN.

[The next letter is of especial interest, as showing how high a value my father placed on the support of the younger German naturalists:]

CHARLES DARWIN TO W. PREYER. (Now Professor of Physiology at Jena.) March 31, 1868.

... I am delighted to hear that you uphold the doctrine of the Modification of Species, and defend my views. The support which I receive from Germany is my chief ground for hoping that our views will ultimately prevail. To the present day I am continually abused or treated with contempt by writers of my own country; but the younger naturalists are almost all on my side, and sooner or later the public must follow those who make the subject their special study. The abuse and contempt of ignorant writers hurts me very little...

CHAPTER 2.VI. — WORK ON 'MAN.'

1864-1870

[In the autobiographical chapter in Volume I., my father gives the circumstances which led to his writing the 'Descent of Man.' He states that his collection of facts, begun in 1837 or 1838, was continued for many years without any definite idea of publishing on the subject. The following letter to Mr. Wallace shows that in the period of ill-health and depression about 1864 he despaired of ever being able to do so:]

CHARLES DARWIN TO A.R. WALLACE. Down, [May?] 28 [1864].

Dear Wallace,

I am so much better that I have just finished a paper for Linnean Society (On the three forms, etc., of Lythrum.); but I am not yet at all strong, I felt much disinclination to write, and therefore you must forgive me for not having sooner thanked you for your paper on 'Man' ('Anthropological Review,' March 1864.), received on the 11th. But first let me say that I have hardly ever in my life been more struck by any paper than that on 'Variation,' etc. etc., in the "Reader". ('"Reader", April 16, 1864. "On the Phenomena of Variation," etc. Abstract of a paper read before the Linnean Society, March 17, 1864.) I feel sure that such papers will do more for the spreading of our views on the modification of species than any separate Treatises on the simple subject itself. It is really admirable; but you ought not in the Man paper to speak of the theory as mine; it is just as much yours as mine. One correspondent has already noticed to me your "high-minded" conduct on this head. But now for your Man paper, about which I should like to write more than I can. The great leading idea is quite new to me, viz. that during late ages, the mind will have been modified more than the body; yet I had got as far as to see with you that the struggle between the races of man depended entirely on intellectual and MORAL qualities. The latter part of the paper I can designate only as grand and most eloquently done. I have shown your paper to two or three persons who have been here, and they have been equally struck with it. I am not sure that I go with you on all minor points: when reading Sir G. Grey's account of the constant battles of Australian savages, I remember thinking that natural selection would come in, and likewise with the Esquimaux, with whom the art of fishing and managing canoes is said to be hereditary. I rather differ on the rank, under a classificatory point of view, which you assign to man; I do not think any character simply in excess ought ever to be used for the higher divisions. Ants would not be separated from other hymenopterous insects, however high the instinct of the one, and however low the instincts of the other. With respect to the differences of race, a conjecture has occurred to me that much may be due to the correlation of complexion (and consequently hair) with constitution. Assume that a dusky individual best escaped miasma, and you will readily see what I mean. I persuaded the Director-General of the Medical Department of the Army to send printed forms to the surgeons of all regiments in tropical countries to ascertain this point, but I dare say I shall never get any returns. Secondly, I suspect that a sort of sexual selection has been the most powerful means of changing the races of man. I can show that the different races have a widely different standard of beauty. Among savages the most powerful men will have the pick of the women, and they will generally leave the most descendants. I have collected a few notes on man, but I do not suppose that I shall ever use them. Do you intend to follow out your views, and if so, would you like at some future time to have my few references and notes? I am sure I hardly know whether they are of any value, and they are at present in a state of chaos.

There is much more that I should like to write, but I have not strength.

Believe me, dear Wallace, yours very sincerely, CH. DARWIN.

P.S. — Our aristocracy is handsomer (more hideous according to a Chinese or Negro) than the middle classes, from (having the) pick of the women; but oh, what a scheme is primogeniture for destroying natural selection! I fear my letter will be barely intelligible to you.

[In February 1867, when the manuscript of 'Animals and Plants' had been sent to Messrs. Clowes to be printed, and before the proofs began to come in, he had an interval of spare time, and began a "chapter on Man," but he soon found it growing under his hands, and determined to publish it separately as a "very small volume."

The work was interrupted by the necessity of correcting the proofs of 'Animals and Plants,' and by some botanical work, but was resumed in the following year, 1868, the moment he could give himself up to it.

He recognized with regret the gradual change in his mind that rendered continuous work more and more necessary to him as he grew older. This is expressed in a letter to Sir J.D. Hooker, June 17, 1868, which repeats to some extent what is expressed in the Autobiography: —

"I am glad you were at the 'Messiah,' it is the one thing that I should like to hear again, but I dare say I should find my soul too dried up to appreciate it as in old days; and then I should feel very flat, for it is a horrid bore to feel as I constantly do, that I am a withered leaf for every subject except Science. It sometimes makes me hate Science, though God knows I ought to be thankful for such a perennial interest, which makes me forget for some hours every day my accursed stomach."

The work on Man was interrupted by illness in the early summer of 1868, and he left home on July 16th for Freshwater, in the Isle of Wight, where he remained with his family until August 21st. Here he made the acquaintance of Mrs. Cameron. She received the whole family with open-hearted kindness and hospitality, and my father always retained a warm feeling of friendship for her. She made an excellent photograph of him, which was published with the inscription written by him: "I like this photograph very much better than any other which has been taken of me." Further interruption occurred in the autumn so that continuous work on the 'Descent of Man' did not begin until 1869. The following letters give some idea of the earlier work in 1867:]

CHARLES DARWIN TO A.R. WALLACE. Down, February 22, [1867?].

My dear Wallace,

I am hard at work on sexual selection, and am driven half mad by the number of collateral points which require investigation, such as the relative number of the two sexes, and especially on polygamy. Can you aid me with respect to birds which have strongly marked secondary sexual characters, such as birds of paradise, humming-birds, the Rupicola, or any other such cases? Many gallinaceous birds certainly are polygamous. I suppose that birds may be known not to be polygamous if they are seen during the whole breeding season to associate in pairs, or if the male incubates or aids in feeding the young. Will you have the kindness to turn this in your mind? But it is a shame to trouble you now that, as I am HEARTILY glad to hear, you are at work on your Malayan travels. I am fearfully puzzled how far to extend your protective views with respect to the females in various classes. The more I work the more important sexual selection apparently comes out.

Can butterflies be polygamous! i.e. will one male impregnate more than one female? Forgive me troubling you, and I dare say I shall have to ask forgiveness again...

CHARLES DARWIN TO A.R. WALLACE. Down, February 23 [1867].

Dear Wallace,

I much regretted that I was unable to call on you, but after Monday I was unable even to leave the house. On Monday evening I called on Bates, and put a difficulty before him, which he could not answer, and, as on some former similar occasion, his first suggestion was, "You had better ask Wallace." My difficulty is, why are caterpillars sometimes so beautifully and artistically coloured? Seeing that many are coloured to escape danger, I can hardly attribute their bright colour in other cases to mere physical conditions. Bates says the most gaudy caterpillar he ever saw in Amazonia (of a sphinx) was conspicuous at the distance of yards, from its black and red colours, whilst feeding on large green leaves. If any one objected to male butterflies having been made beautiful by sexual selection, and asked why should they not have been made beautiful as well as their caterpillars, what would you answer? I could not answer, but should maintain my ground. Will you think over this, and some time, either by letter or when we meet, tell me what you think? Also I want to know whether your FEMALE mimetic butterfly is more beautiful and brighter than the male. When next in London I must get you to show me your kingfishers. My health is a dreadful evil; I failed in half my engagements during this last visit to London.

Believe me, yours very sincerely, C. DARWIN.

CHARLES DARWIN TO A.R. WALLACE. Down, February 26 [1867].

My dear Wallace,

Bates was quite right; you are the man to apply to in a difficulty. I never heard anything more ingenious than your suggestion (The suggestion that conspicuous caterpillars or perfect insects (e.g. white butterflies), which are distasteful to birds, are protected by being easily recognised and avoided. See Mr. Wallace's 'Natural Selection,' 2nd edition, page 117.), and I hope you may be able to prove it true. That is a splendid fact about the white moths; it warms one's very blood to see a theory thus almost proved to be true. (Mr. Jenner Weir's observations published in the Transactions of the Entomolog. Soc. (1869 and 1870) give strong support to the theory in question.) With respect to the beauty of male butterflies, I must as yet think it is due to sexual selection. There is some evidence that dragon-flies are attracted by bright colours; but what leads me to the above belief is, so many male Orthoptera and Cicadas having musical instruments. This being the case, the analogy of birds makes me believe in sexual selection with respect to colour in insects. I wish I had strength and time to make some of the experiments suggested by you, but I thought butterflies would not pair in confinement. I am sure I have heard of some such difficulty. Many years ago I had a dragon-fly painted with gorgeous colours, but I never had an opportunity of fairly trying it.

The reason of my being so much interested just at present about sexual selection is, that I have almost resolved to publish a little essay on the origin of Mankind, and I still strongly think (though I failed to convince you, and this, to me, is the heaviest blow possible) that sexual selection has been the main agent in forming the races of man.

By the way, there is another subject which I shall introduce in my essay, namely, expression of countenance. Now, do you happen to know by any odd chance a very good-natured and acute observer in the Malay Archipelago, who you think would make a few easy observations for me on the expression of the Malays when excited by various emotions? For in this case I would send to such person a list of queries. I thank you for your most interesting letter, and remain,

Yours very sincerely, CH. DARWIN.

CHARLES DARWIN TO A.R. WALLACE. Down, March [1867].

My dear Wallace,

I thank you much for your two notes. The case of Julia Pastrana (A bearded woman having an irregular double set of teeth. 'Animals and Plants,' volume ii. page 328.) is a splendid addition to my other cases of correlated teeth and hair, and I will add it in correcting the press of my present volume. Pray let me hear in the course of the summer if you get any evidence about the gaudy caterpillars. I should much like to give (or quote if published) this idea of yours, if in any way supported, as suggested by you. It will, however, be a long time hence, for I can see that sexual selection is growing into quite a large subject, which I shall introduce into my essay on Man, supposing that I ever publish it. I had intended giving a chapter on man, inasmuch as many call him (not QUITE truly) an eminently domesticated animal, but I found the subject too large for a chapter. Nor shall I be capable of treating the subject well, and my sole reason for taking it up is, that I am pretty well convinced that sexual selection has played an important part in the formation of races, and sexual selection has always been a subject which has interested me much. I have been very glad to see your impression from memory on the expression of Malays. I fully agree with you that the subject is in no way an important one; it is simply a "hobby-horse" with me, about twenty-seven years old; and AFTER thinking that I would write an essay on man, it flashed on me that I could work in some "supplemental remarks on expression." After the horrid, tedious, dull work of my present huge, and I fear unreadable, book ['The Variation of Animals and Plants'], I thought I would amuse myself with my hobby-horse. The subject is, I think, more curious and more amenable to scientific treatment than you seem willing to allow. I want, anyhow, to upset Sir C. Bell's view, given in his most interesting work, 'The Anatomy of Expression,' that certain muscles have been given to man solely that he may reveal to other men his feelings. I want to try and show how expressions have arisen. That is a good suggestion about newspapers, but my experience tells me that private applications are generally most fruitful. I will, however, see if I can get the queries inserted in some Indian paper. I do not know the names or addresses of any other papers.

... My two female amanuenses are busy with friends, and I fear this scrawl will give you much trouble to read. With many thanks,

Yours very sincerely, CH. DARWIN.

[The following letter may be worth giving, as an example of his sources of information, and as showing what were the thoughts at this time occupying him:]

CHARLES DARWIN TO F. MULLER. Down, February 22 [1867].

... Many thanks for all the curious facts about the unequal number of the sexes in Crustacea, but the more I investigate this subject the deeper I sink in doubt and difficulty. Thanks also for the confirmation of the rivalry of Cicadae. I have often reflected with surprise on the diversity of the means for producing music with insects, and still more with birds. We thus get a high idea of the importance of song in the animal kingdom. Please to tell me where I can find any account of the auditory organs in the Orthoptera. Your facts are quite new to me. Scudder has described an insect in the Devonian strata, furnished with a stridulating apparatus. I believe he is to be trusted, and, if so, the apparatus is of astonishing antiquity. After reading Landois's paper I have been working at the stridulating organ in the Lamellicorn beetles, in expectation of finding it sexual; but I have only found it as yet in two cases, and in these it was equally developed in both sexes. I wish you would look at any of your common lamellicorns, and take hold of both males and females, and observe whether they make the squeaking or grating noise equally. If they do not, you could, perhaps, send me a male and female in a light little box. How curious it is that there should be a special organ for an object apparently so unimportant as squeaking. Here is another point; have you any toucans? if so, ask any trustworthy hunter whether the beaks of the males, or of both sexes, are more brightly coloured during the breeding season than at other times of the year... Heaven knows whether I shall ever live to make use of half the valuable facts which you have communicated to me! Your paper on Balanus armatus, translated by Mr. Dallas, has just appeared in our 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History,' and I have read it with the greatest interest. I never thought that I should live to hear of a hybrid Balanus! I am very glad that you have seen the cement tubes; they appear to me extremely curious, and, as far as I know, you are the first man who has verified my observations on this point.

With most cordial thanks for all your kindness, my dear Sir,

Yours very sincerely, C. DARWIN.

CHARLES DARWIN TO A. DE CANDOLLE. Down, July 6, 1868.

My dear Sir,

I return you my SINCERE thanks for your long letter, which I consider a great compliment, and which is quite full of most interesting facts and views. Your references and remarks will be of great use should a new edition of my book ('Variation of Animals and Plants.') be demanded, but this is hardly probable, for the whole edition was sold within the first week, and another large edition immediately reprinted, which I should think would supply the demand for ever. You ask me when I shall publish on the 'Variation of Species in a State of Nature.' I have had the MS. for another volume almost ready during several years, but I was so much fatigued by my last book that I determined to amuse myself by publishing a short essay on the 'Descent of Man.' I was partly led to do this by having been taunted that I concealed my views, but chiefly from the interest which I had long taken in the subject. Now this essay has branched out into some collateral subjects, and I suppose will take me more than a year to complete. I shall then begin on 'Species,' but my health makes me a very slow workman. I hope that you will excuse these details, which I have given to show that you will have plenty of time to publish your views first, which will be a great advantage to me. Of all the curious facts which you mention in your letter, I think that of the strong inheritance of the scalp-muscles has interested me most. I presume that you would not object to my giving this very curious case on your authority. As I believe all anatomists look at the scalp-muscles as a remnant of the Panniculus carnosus which is common to all the lower quadrupeds, I should look at the unusual development and inheritance of these muscles as probably a case of reversion. Your observation on so many remarkable men in noble families having been illegitimate is extremely curious; and should I ever meet any one capable of writing an essay on this subject, I will mention your remarks as a good suggestion. Dr. Hooker has several times remarked to me that morals and politics would be very interesting if discussed like any branch of natural history, and this is nearly to the same effect with your remarks...

CHARLES DARWIN TO L. AGASSIZ. Down, August 19, 1868.

Dear Sir,

I thank you cordially for your very kind letter. I certainly thought that you had formed so low an opinion of my scientific work that it might have appeared indelicate in me to have asked for information from you, but it never occurred to me that my letter would have been shown to you. I have never for a moment doubted your kindness and generosity, and I hope you will not think it presumption in me to say, that when we met, many years ago, at the British Association at Southampton, I felt for you the warmest admiration.

Your information on the Amazonian fishes has interested me EXTREMELY, and tells me exactly what I wanted to know. I was aware, through notes given me by Dr. Gunther, that many fishes differed sexually in colour and other characters, but I was particularly anxious to learn how far this was the case with those fishes in which the male, differently from what occurs with most birds, takes the largest share in the care of the ova and young. Your letter has not only interested me much, but has greatly gratified me in other respects, and I return you my sincere thanks for your kindness. Pray believe me, my dear Sir,

Yours very faithfully, CHARLES DARWIN.

CHARLES DARWIN TO J.D. HOOKER. Down, Sunday, August 23 [1868].

My dear old Friend,

I have received your note. I can hardly say how pleased I have been at the success of your address (Sir Joseph Hooker was President of the British Association at the Norwich Meeting in 1868.), and of the whole meeting. I have seen the "Times", "Telegraph", "Spectator", and "Athenaeum", and have heard of other favourable newspapers, and have ordered a bundle. There is a "chorus of praise." The "Times" reported miserably, i.e. as far as errata was concerned; but I was very glad at the leader, for I thought the way you brought in the megalithic monuments most happy. (The British Association was desirous of interesting the Government in certain modern cromlech builders, the Khasia race of East Bengal, in order that their megalithic monuments might be efficiently described.) I particularly admired Tyndall's little speech (Professor Tyndall was President of Section A.)... The "Spectator" pitches a little into you about Theology, in accordance with its usual spirit...

Your great success has rejoiced my heart. I have just carefully read the whole address in the "Athenaeum"; and though, as you know, I liked it very much when you read it to me, yet, as I was trying all the time to find fault, I missed to a certain extent the effect as a whole; and this now appears to me most striking and excellent. How you must rejoice at all your bothering labour and anxiety having had so grand an end. I must say a word about myself; never has such a eulogium been passed on me, and it makes me very proud. I cannot get over my AMAZEMENT at what you say about my botanical work. By Jove, as far as my memory goes, you have strengthened instead of weakened some of the expressions. What is far more important than anything personal, is the conviction which I feel that you will have immensely advanced the belief in the evolution of species. This will follow from the publicity of the occasion, your position, so responsible, as President, and your own high reputation. It will make a great step in public opinion, I feel sure, and I had not thought of this before. The "Athenaeum" takes your snubbing (Sir Joseph Hooker made some reference to the review of 'Animals and Plants' in the "Athenaeum" of February 15, 1868.) with the utmost mildness. I certainly do rejoice over the snubbing, and hope [the reviewer] will feel it a little. Whenever you have SPARE time to write again, tell me whether any astronomers (In discussing the astronomer's objection to Evolution, namely that our globe has not existed for a long enough period to give time for the assumed transmutation of living beings, Hooker challenged Whewell's dictum that, astronomy is the queen of sciences — the only perfect science.) took your remarks in ill part; as they now stand they do not seem at all too harsh and presumptuous. Many of your sentences strike me as extremely felicitous and eloquent. That of Lyell's "under-pinning" (After a eulogium on Sir Charles Lyell's heroic renunciation of his old views in accepting Evolution, Sir J.D. Hooker continued, "Well may he be proud of a superstructure, raised on the foundations of an insecure doctrine, when he finds that he can underpin it and substitute a new foundation; and after all is finished, survey his edifice, not only more secure but more harmonious in its proportion than it was before."), is capital. Tell me, was Lyell pleased? I am so glad that you remembered my old dedication. (The 'Naturalist's Voyage' was dedicated to Lyell.) Was Wallace pleased?

How about photographs? Can you spare time for a line to our dear Mrs. Cameron? She came to see us off, and loaded us with presents of photographs, and Erasmus called after her, "Mrs. Cameron, there are six people in this house all in love with you." When I paid her, she cried out, "Oh what a lot of money!" and ran to boast to her husband.

I must not write any more, though I am in tremendous spirits at your brilliant success.

Yours ever affectionately, C. DARWIN.

[In the "Athenaeum" of November 29, 1868, appeared an article which was in fact a reply to Sir Joseph Hooker's remarks at Norwich. He seems to have consulted my father as to the wisdom of answering the article. My father wrote on September 1:

"In my opinion Dr. Joseph Dalton Hooker need take no notice of the attack in the "Athenaeum" in reference to Mr. Charles Darwin. What an ass the man is to think he cuts one to the quick by giving one's Christian name in full. How transparently false is the statement that my sole groundwork is from pigeons, because I state I have worked them out more fully than other beings! He muddles together two books of Flourens."

The following letter refers to a paper ('Transactions of the Ottawa Academy of Natural Sciences,' 1868, by John D. Caton, late Chief Justice of Illinois.) by Judge Caton, of which my father often spoke with admiration:]

CHARLES DARWIN TO JOHN D. CATON. Down, September 18, 1868.

Dear Sir,

I beg leave to thank you very sincerely for your kindness in sending me, through Mr. Walsh, your admirable paper on American Deer.

It is quite full of most interesting observations, stated with the greatest clearness. I have seldom read a paper with more interest, for it abounds with facts of direct use for my work. Many of them consist of little points which hardly any one besides yourself has observed, or perceived the importance of recording. I would instance the age at which the horns are developed (a point on which I have lately been in vain searching for information), the rudiment of horns in the female elk, and especially the different nature of the plants devoured by the deer and elk, and several other points. With cordial thanks for the pleasure and instruction which you have afforded me, and with high respect for your power of observation, I beg leave to remain, dear Sir,

Yours faithfully and obliged, CHARLES DARWIN.

[The following extract from a letter (September 24, 1868) to the Marquis de Saporta, the eminent palaeo-botanist, refers to the growth of evolutionary views in France (In 1868 he was pleased at being asked to authorise a French translation of his 'Naturalist's Voyage.': —

"As I have formerly read with great interest many of your papers on fossil plants, you may believe with what high satisfaction I hear that you are a believer in the gradual evolution of species. I had supposed that my book on the 'Origin of Species' had made very little impression in France, and therefore it delights me to hear a different statement from you. All the great authorities of the Institute seem firmly resolved to believe in the immutability of species, and this has always astonished me... almost the one exception, as far as I know, is M. Gaudry, and I think he will be soon one of the chief leaders in Zoological Palaeontology in Europe; and now I am delighted to hear that in the sister department of Botany you take nearly the same view."]

CHARLES DARWIN TO E. HAECKEL. Down, November 19 [1868].

My dear Haeckel,

I must write to you again, for two reasons. Firstly, to thank you for your letter about your baby, which has quite charmed both me and my wife; I heartily congratulate you on its birth. I remember being surprised in my own case how soon the paternal instincts became developed, and in you they seem to be unusually strong... I hope the large blue eyes and the principles of inheritance will make your child as good a naturalist as you are; but, judging from my own experience, you will be astonished to find how the whole mental disposition of your children changes with advancing years. A young child, and the same when nearly grown, sometimes differ almost as much as do a caterpillar and butterfly.

The second point is to congratulate you on the projected translation of your great work ('Generelle Morphologie,' 1866. No English translation of this book has appeared.), about which I heard from Huxley last Sunday. I am heartily glad of it, but how it has been brought about, I know not, for a friend who supported the supposed translation at Norwich, told me he thought there would be no chance of it. Huxley tells me that you consent to omit and shorten some parts, and I am confident that this is very wise. As I know your object is to instruct the public, you will assuredly thus get many more readers in England. Indeed, I believe that almost every book would be improved by condensation. I have been reading a good deal of your last book ('Die Naturliche Schopfungs-Geschichte,' 1868. It was translated and published in 1876, under the title, 'The History of Creation.'), and the style is beautifully clear and easy to me; but why it should differ so much in this respect from your great work I cannot imagine. I have not yet read the first part, but began with the chapter on Lyell and myself, which you will easily believe pleased me VERY MUCH. I think Lyell, who was apparently much pleased by your sending him a copy, is also much gratified by this chapter. (See Lyell's interesting letter to Haeckel. 'Life of Sir C. Lyell,' ii. page 435.) Your chapters on the affinities and genealogy of the animal kingdom strike me as admirable and full of original thought. Your boldness, however, sometimes makes me tremble, but as Huxley remarked, some one must be bold enough to make a beginning in drawing up tables of descent. Although you fully admit the imperfection of the geological record, yet Huxley agreed with me in thinking that you are sometimes rather rash in venturing to say at what periods the several groups first appeared. I have this advantage over you, that I remember how wonderfully different any statement on this subject made 20 years ago, would have been to what would now be the case, and I expect the next 20 years will make quite as great a difference. Reflect on the monocotyledonous plant just discovered in the PRIMORDIAL formation in Sweden.